The Office Was a Gas Station: Wild Alabama and the New Forest Conservation in the South

In the 1980's and 1990's, forests in the Southern Region was a sacrifice zone for the National Forest timber program target goals. The standards in the agency were far below most other regions, with timber sales often having clearcuts totalling hundreds of acres, often with little compliance with agency standards. Environmental Analyses would often be a few pages of boilerplate. Mandates to monitor the health of sensitive species was often absent. Some forests, like the DeSoto in Mississippi, had runaway road volume densities of ten or more square miles of road per square mile of forest. A great deal of the landscape was being turned into loblolly pine plantations.

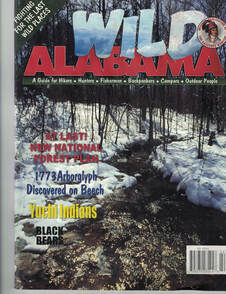

In the Bankhead National Forest in northwest Alabama, a few locals began to organize. Lamar Marshall, who worked at chemical plant, was an outdoors enthusiast who decided a new approach to forest advocacy was needed. He drew together the local knowledge of the and cultural history of the area to go beyond normal roundtable meetings with the Forest Service. Recognizing that bringing attention to this previously little-known forest would potentially expand a base of support he founded the Bankhead Monitor, a monthly magazine that was meant to showcase the Bankhead's wild and scenic beauty, history, and recreational opportunities. However, by mixing in serious analysis of forest policy and laws, action alerts about pending timber sales, and critiques of land management orthodoxy, the Monitor was a unique way of not only publicizing the forest, but educating the public about the complex issues the forest faced.

"I first saw the Bankhead Monitor at a Piggly Wiggly grocery store newsstand in rural Mississippi," says Davis Mounger of Tennessee Heartwood and the Sierra Club. "I was new to forest activism, and I just didn't know where to begin. Suddenly out of nowhere is this magazine in a rural grocery store that laid out the issues on public lands and how to deal with them."

By then, Marshall's work had come to the attention of attorney Ray Vaughan. Working together to mix populist advocacy with a smart engagement with government and the courts, they began to not only bring reform to the Bankhead, but soon expanded their base to all of Alabama's public lands. The Monitor soon became Wild Alabama, and Vaughan's law firm Wildlaw, began empowering attorneys, environmental groups, and common citizens in how to use their NEPA rights to weigh in on how their forests were being treated. "They got into some out-of the box thinking," says Mounger. "At one point Lamar had his headquarters in Lawrence County in a gas station he ran. You could buy gas, beer, cokes, deep ecology books, hunting and fishing gear, or arrange wildflower or cultural heritage tours of the forest. It wasn't your typical country gas station."

In the Bankhead National Forest in northwest Alabama, a few locals began to organize. Lamar Marshall, who worked at chemical plant, was an outdoors enthusiast who decided a new approach to forest advocacy was needed. He drew together the local knowledge of the and cultural history of the area to go beyond normal roundtable meetings with the Forest Service. Recognizing that bringing attention to this previously little-known forest would potentially expand a base of support he founded the Bankhead Monitor, a monthly magazine that was meant to showcase the Bankhead's wild and scenic beauty, history, and recreational opportunities. However, by mixing in serious analysis of forest policy and laws, action alerts about pending timber sales, and critiques of land management orthodoxy, the Monitor was a unique way of not only publicizing the forest, but educating the public about the complex issues the forest faced.

"I first saw the Bankhead Monitor at a Piggly Wiggly grocery store newsstand in rural Mississippi," says Davis Mounger of Tennessee Heartwood and the Sierra Club. "I was new to forest activism, and I just didn't know where to begin. Suddenly out of nowhere is this magazine in a rural grocery store that laid out the issues on public lands and how to deal with them."

By then, Marshall's work had come to the attention of attorney Ray Vaughan. Working together to mix populist advocacy with a smart engagement with government and the courts, they began to not only bring reform to the Bankhead, but soon expanded their base to all of Alabama's public lands. The Monitor soon became Wild Alabama, and Vaughan's law firm Wildlaw, began empowering attorneys, environmental groups, and common citizens in how to use their NEPA rights to weigh in on how their forests were being treated. "They got into some out-of the box thinking," says Mounger. "At one point Lamar had his headquarters in Lawrence County in a gas station he ran. You could buy gas, beer, cokes, deep ecology books, hunting and fishing gear, or arrange wildflower or cultural heritage tours of the forest. It wasn't your typical country gas station."

Mounger credits the folks in Alabama for bringing reform throughout the South: "Ray and Lamar would tour around the South and explain to people how National Forests were managed, the agency lingo, the realities of subsidized timber programs, how to write a FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) request so they could uncover what was really going on. Lots of groups either got started or got off the ground thanks to their help. I've beeen working on forest issues for twenty five years, and much of how I operate I can trace back to the help they gave me. They taught me how to do legal and science citations, write an appeal, work on a court case, how to analyze a timber sale, and plain talk to government officials. It was the civics class you should have had in high school."

So successful was their work that the entire Southern region declared a moratorium on timber cutting until important standards were raised. Many challenges remain for National Forests in the South, but the situation on the ground is a far cry from what it was two decades ago. The legacy of Wild Alabama and Wild Law continues in numerous conservation groups and activists throughout the region and forests that get the appreciation they deserve.

So successful was their work that the entire Southern region declared a moratorium on timber cutting until important standards were raised. Many challenges remain for National Forests in the South, but the situation on the ground is a far cry from what it was two decades ago. The legacy of Wild Alabama and Wild Law continues in numerous conservation groups and activists throughout the region and forests that get the appreciation they deserve.